Tangible world heritage site

Lalibela Rock Churches- A Kingdom of the Living Rock

Lalibela is a town in northern Ethiopia that is famous for its monolithic rock-cut churches. Lalibela is one of Ethiopia's holiest cities, second only to Aksum, and is a center of pilgrimage for much of the country. Unlike Aksum, the population of Lalibela is almost completely Ethiopian Orthodox Christian. The layout and names of the major buildings in Lalibela are widely accepted, especially by the local clergy, to be a symbolic representation of Jerusalem. This has led some experts to date the current form of its churches to the years following the capture of Jerusalem in 1187 by the Muslim soldier Saladin.

Lalibela is located in the Semien Wollo Zone of the Amhara ethnic division (or kilil) at roughly 2,500 meters above sea level. It is the main town in Lasta woreda, which was formerly part of Bugna woreda.

History

During the reign of Saint Gebre Mesqel Lalibela (a member of the Zagwe Dynasty, who ruled Ethiopia in the late 12th century and early 13th century) the current town of Lalibela was known as Roha. The saintly king was given this name due to a swarm of bees said to have surrounded him at his birth, which his mother took as a sign of his future reign as Emperor of Ethiopia. The names of several places in the modern town and the general layout of the rock-cut churches themselves are said to mimic names and patterns observed by Lalibela during the time he spent in Jerusalem and the Holy Land as a youth.

Lalibela is said to have seen Jerusalem and then attempted to build a new Jerusalem as his capital in response to the capture of old Jerusalem by Muslims in 1187. As such, many features have Biblical names – even the town's river is known as the River Jordan. It remained the capital of Ethiopia from the late 12th century and into the 13th century.

The first European to see these churches was the Portuguese explorer Pêro da Covilhã (1460–1526). Portuguese priest Francisco Álvares (1465–1540), who accompanied the Portuguese Ambassador on his visit to Lebna Dengel in the 1520s. His description of these structures concludes:

Rock-Hewn Churches, Lalibela

The 11 medieval monolithic cave churches of this 13th-century 'New Jerusalem' are situated in a mountainous region in the heart of Ethiopia near a traditional village with circular-shaped dwellings. Lalibela is a high place of Ethiopian Christianity, still today a place of pilmigrage and devotion.

The rock-hewn churches of Lalibela are exceptionally fine examples of a long-established Ethiopian building tradition. Monolithic churches are to be found all over the north and the centre of the country. Some of the oldest of such churches are to be found in Tigray, where some are believed to date from around the 6th or 7th centuries. King Lalibela is believed to have commissioned these structures with the purpose of creating a holy and symbolic place which considerably influenced Ethiopian religious beliefs.

The 11 medieval monolithic cave churches of this 13th-century 'New Jerusalem' are situated in a mountainous region in the heart of Ethiopia near a traditional village with circular-shaped dwellings. Lalibela is a high place of Ethiopian Christianity, still today a place of pilgrimage and devotion.

Lalibela is a small town at an altitude of almost 2,800 m in the Ethiopian highlands. It is surrounded by a rocky, dry area. Here in the 13th century devout Christians began hewing out the red volcanic rock to create 13 churches. Four of them were finished as completely free-standing structures, attached to their mother rock only at their bases. The remaining nine range from semi-detached to ones whose facades are the only features that have been 'liberated' from the rock.

The Jerusalem theme is important. The rock churches, although connected to one another by maze-like tunnels, are physically separated by a small river which the Ethiopians named the Jordan. Churches on one side of the Jordan represent the earthly Jerusalem; whereas those on the other side represent the heavenly Jerusalem, the city of jewels and golden sidewalks alluded to in the Bible.

It was King Lalibela who commissioned the structures, but scholars disagree as to his motivation. According to a legendary account, King Lalibela was born in Roha. His name means 'the bee recognizes its sovereignty'. God ordered him to build 10 monolithic churches, and gave him detailed instructions as to their construction and even their colours. When his brother Harbay abdicated, the time had come for Lalibela to fulfil this command. Construction work began and is said to have been carried out with remarkable speed, which is scarcely surprising, for, according to legend, angels joined the labourers by day and at night did double the amount of work which the men had done during the hours of daylight.

Like more episodes in the long history of this country, there are many legends about this king. One is that Lalibela was poisoned by his brother and fell into a three-day coma in which he was taken to Heaven and given a vision of rock-hewn cities. Another legend says that he went into exile to Jerusalem and vowed that when he returned he would create a New Jerusalem. Others attribute the building of the churches to Templars from Europe.

The names of the churches evoke hints of Hebrew, a language related to the Hamo-Semitic dialect still used in Ethiopian church liturgies: Beta Medhane Alem (House of the Saviour of the World), Beta Qedus Mikael (House of St Michael) and Beta Amanuel (House of Emmanuel) are all reminiscent of the Hebrew beth (house). In one of the churches there is a pillar covered with cotton. A monk had a dream in which he saw Christ kissing it; according to the monks, the past, the present and the future are carved into it. The churches are connected to each other by small passages and tunnels.

Simien Mountains National Park- the roof of Africa

This park is registered as a World Heritage site by UNESCO. Located in the Simien Mountains, it occupies a surface area of 420 square kilometers. Simien means “north” in Amharic, an allusion to the position it occupies in the Gondar massif, one of the craggiest in Africa. The park is interesting because of the uniqueness of its endemic animals the beauty of its flora, and the majesty of its impressive landscape.

The park, situated between 4,430 and 1,900 metres (6,200-4,500 feet), boasts varied flora with three marked botanical areas. The highest parts have meadows with little vegetation, characteristic of Afro alpine zones. Here we can find the endemic Lobelia rhynchopetalum, small groups of perpetual flowers, Helichrysum, and the striking Kniphofia foliosa. Of particular botanical interest is the Afrovivella semiensis, a small fleshy plant with pink flowers in the shape of little bells. This plant has been found only in the Simien mountains and nohere else on earth. There is only one species within its genus.

As the landscape desends, it starts to darken with scrub species, including the giant heather, Saint John’s Wort trees, Juniperus, and podocarpus. The prized Hagenia abyssinica is often seen decorated with the little white flowers of the climbing plant clematis (Clematis randiflora). The air is permeated by the scent of the Rosa abyssinica, which takes the form of a tree in this region.

In the park, we can find three of the most colourful endemic mammals in Ethiopia: the Walia ibex which lives wild at an altitude of more than 2,500 meters, the gelada baboon which inhabits the Simien Plateaux, and the Ethiopian Wolf (Simien Wolf), which is also found in great numbers in the Bale Mountains.

In the northern part, the massif drops sharply away into a canyon. Here, it is not difficult to spot the curious walia ibex on the slopes of its last refuge. This wild goat weights abour 120 kilogrammes. Its coat is dark brown and its majestic curved-back horns can grow to more than one metre long. About 500 of these goats are believed to still exist, but the protection provided by the park gives hope that the population will increase.

The endemic gelada baboons are found throughout the Simien Plateaux. They can be seen in open, craggy areas between 2,000 and 4,000 metres, often close to precipices and ravines in case danger threatens. Ch’elada or gelada refers to the patch of red hairless skin on the chest and throat. In females, this skin becomes inflamed when they are in heat. It is also known as the lion monkey because its striking mane makes it look like the big cat. The male has a large head and a snubbed snout and measures between 75 and 80 centimeters long. The female is approximately half the size of the male. The males are armed with powerful fangs. They are slender but strong, and their shoulders are covered with long dark hair. They are above all terrestrial and strictly vegetarian, feeding on grasses and bulbs. These gregarious creatures form troops of up to 400 individuals, in which each adult male has a harem of females. Other mammals which can be seen in the park include the klipspringer, the grey duiker, hyenas, and golden jackals.

Approximately 50 different bird species have been identified, among them a great many scavengers and birds of prey. Birds migrating from Europe and all over Africa also can be seen here. One of the most striking birds is the large and powerful lammergeyer or bearded vulture. It is a scavenger, often seen on the north face of the park. This bird nests on inaccessible shelves and in hollows on great walls of rock. Unlike other vultures, its head is completely covered in feathers. Underneath its beak, it has a streak of stiff bristles, which accounts for its nickname “bearded vulture.” Its wingspan can reach up to 250 centimetres. The lammergeyer feeds on animal remains stripped of meat by other vultures. It takes the bones, drops them from a great height, and eats the marrow. Bones and marrow comprise 85% of its diet.

Many other birds of prey can be seen: Buzzards, Egyptian vultures, Ruppel’s griffon vultures, hooded vultures, eagles, falcons, and ravens. Within the endemic species there are the thick-billed raven, the wattled ibis and the white-collared pigeon. Other endemic species such as the spot-breasted plover, the white-billed starling and the black-headed siskin are easy to spot in this region during the rainy season, as they search for food over the cultivated land of the high plateaux. In the valleys, one can see black-headed forest orioles and golden-backed woodpeckers.

Maximum temperatures during the day are about 15 degree centigrade (60 degree Fahrenheit). At night the temperature usually drops to 3 degree –5 degree centigrade (35 degree-40 degree Fahrenheit). October, November and December are the coldest month, when the temperature is likely to go below freezing. The season of the big rains begins in June and lasts through September. Travel is difficult duing this this time.

Gondar- the Camelot of Africa

The World Heritage site is an outstanding testimony of the modern Ethiopian civilization on the northern plateau of Tana. The characteristics of the style of the Gondar period appeared at the beginning of the 17th century in the capital city and have subsequently marked Ethiopian architecture in a long-lasting manner.

Flanked by twin mountain streams at an altitude of more than 2,300 m, Gondar was founded by Emperor Fasilidas who, tiring of the pattern of migration that had characterized the lifestyle of so many of his forefathers, moved his capital here in 1636, a role that it filled until 1864. It is famous for its many medieval castles and the design and decoration of its churches. No one knows exactly why Fasilidas chose to establish his headquarters there. Some legends say an archangel prophesied that an Ethiopian capital would be built at a place with a name that began with the letter G. The legend led to a whole series of 16th- and 17th-century towns: Guzara, Gorgora, and finally Gondar. Another legend claims that the city was built in a place chosen by God, who pointed it out to Fasilidas who had followed a buffalo there when hunting.

The main castle, which stands today in a grassy compound surrounded by later fortresses, was built in the late 1630s and early 1640s on the orders of Fasilidas. With its huge towers and looming battlemented walls, it resembles a piece of medieval Europe transposed to Ethiopia. In addition to this castle, Fasiladas is said to have been responsible for the building of a number of other structures, perhaps the oldest of which is the Enqulal Gemb (Egg Castle), so named on account of its egg-shaped domed roof.

Beyond the confines of the city to the north-west by the Qaha River there is another fine building sometimes associated by Fasilidas, a bathing palace. The building is a two-storeyed battlemented structure situated within and on one side of a rectangular pool of water which was supplied by a canal from the nearby river. The bathing pavilion itself stands on pier arches, and contains several rooms reached by a stone bridge, part of which could be raised for defence. The Emperor, who was greatly interested in architecture was also responsible for seven churches and a number of bridges.

Iyasu the Great, a grandson of Fasilidas, was particularly active. His castle was described at the time as finer than the House of Solomon. Its inner walls were decorated with ivory, mirrors and paintings of palm trees and its ceiling was covered with gold-leaf and precious stones. Iyasu's most lasting achievement was the Church of Debra Berhan Selassie (Light of the Trinity), which stands surrounded by a high wall on raised ground to the north-west of the city and continues in regular use. A plain, thatched, rectangular structure on the outside, the interior of Debra Berhan Selassie is marvellously painted with scenes from religious history. The north wall is dominated by a depiction of the Trinity above the Crucifixion; the theme of the south wall is St Mary and that of the east wall the life of Jesus. The west wall shows major saints, with St George in red and gold on a prancing white horse.

Not long after completing this remarkable and impressive work, Iyasu went into deep depression when his favourite concubine died. He abandoned affairs of state and his son, Tekla Haimanot, declared himself Emperor and killed his father. Tekla Haimanot was in his turn murdered; his successor was also forcibly deposed and the next monarch was poisoned. The brutalities came to an end with Emperor Bakaffa, who left two fine castles, one attributed directly to him and the other to his consort, the Empress Mentewab.

Bakaffa's successor, Iyasu II, is regarded by most historians as the last of the Gondar Emperors to rule with full authority. During his reign, work began on a whole range of new buildings outside the main palace compound. The monarch also developed the hills north-west of the city centre known as Kweskwam (after the home of the Virgin Mary).

Aksum- the Ancient Kingdom

The ruins of the ancient city of Aksum are located close to Ethiopia's northern border. They mark the location of the heart of ancient Ethiopia, when the Kingdom of Aksum was the most powerful state between the Eastern Roman Empire and Persia. The massive ruins, dating from between the 1st and 13th centuries, include monolithic obelisks, giant stelae, royal tombs and the ruins of ancient castles. Long after its political decline in the 10th century, Ethiopian emperors continued to be crowned in Aksum.

Beginning around the 2nd millennium BCE and continuing until the 4th century CE there was immigration into the Ethiopian region. The immigrants came mostly from a region of western Yemen associated with the Sabean culture. Conditions in their homelands were most probably so harsh that the only means of escape was by a direct route across the Red Sea into Eritrea. By the 4th century, Aksum was already at its peak in land sovereignty, which included most of southern Yemen.

The city of Aksum emerged several centuries before the birth of Christ, as the capital of a state that traded with ancient Greece, Egypt and Asia. With its fleets sailing as far afield as Ceylon, Aksum later became the most important power between the Roman Empire and Persia, and for a while controlled parts of South Arabia. Aksum, whose name first appears in the 1st century AD in the Periplus of the Eritrean Sea, is considered to be the heart of ancient Ethiopia. Indeed, the kingdom which held sway over this area at this time took its name from the city. The ruins of the site spread over a large area and are composed of tall, obelisk-like stelae of imposing height, an enormous table of stone, vestiges of columns and royal tombs inscribed with Aksumite legends and traditions. In the western sector of the city there are also the ruins of three castles from the 1st century AD.

The earliest records and legends suggest that it was from Aksum that Makeda, the fabled Queen of Sheba, journeyed to visit King Solomon in Jerusalem. A son was born to the queen from her union with Solomon. This son, Menelik I, grew up in Ethiopia but travelled to Jerusalem as a young man, where he spent several years before returning to his own country with the Ark of the Covenant. The Ark, according to Ethiopian belief, has remained in Aksum ever since (in an annex to the Church of St Mary of Zion).

In addition to the old St Mary of Zion church, there are many other remains in Aksum dating back to pre- and early Christian times. Among these, a series of inscriptions on stone tablets have proved to be of immense importance to historians of the ancient world. They include a trilingual text in Greek, Sabaean (the language of South Arabia) and Ge'ez (classical Ethiopian), ordered by King Ezana in the 4th century AD, along with the 3,000-year-old stelae and obelisks. The standing obelisk rises to a height of over 23 m and is exquisitely carved to represent a nine-storey building in the fashion of the 'tower-houses' of southern Arabia.

Aksum inherited a culture highly influenced by southern Arabia. The Aksumites' language, Ge'ez, was a modified version of the southern Arabian rudiments, with admixtures of Greek and perhaps Cushitic tongues already present in the region. Their architectural art was inherited from southern Arabian art; some Aksumite artwork contained combinations of Middle Eastern deities.

From its capital on the Tigray Plateau, Aksum was in command of the ivory trade with Sudan. It also dominated the trade route leading south and the port of Adulis on the Gulf of Zola. Its success depended on resourceful techniques, the production of coins, steady migrations of Graeco-Roman merchants and ships landing at the port of Adulis. In exchange for Aksum's goods, traders offered many kinds of cloth, jewellery and metals, especially steel for weapons.

At its peak, Aksum controlled territories as far as southern Egypt, east to the Gulf of Aden, south to the Omo River, and west to the Cushite Kingdom of Meroë. The South Arabian kingdom of the Himyarites was also under the control of Aksum. Unlike the nobility, the people used salt and iron bars as money and barter remained their main source of commerce.

Harar- A walled City of Stone Houses

The walls surrounding this sacred Muslim city were built between the 13th and 16th centuries. Harar Jugol, said to be the fourth holiest city of Islam, numbers 82 mosques, three of which date from the 10th century, and 102 shrines. The most common houses in Harar Jugol are traditional townhouses consisting of three rooms on the ground floor and service areas in the courtyard. Another type of house, called the Indian House, built by Indian merchants who came to Harar after 1887, is a simple rectangular two-storied building with a veranda overlooking either street or courtyard. A third type of building was born of the combination of elements from the other two. The Harari people are known for the quality of their handicrafts, including weaving, basket making and book-binding, but the houses with their exceptional interior design constitute the most spectacular part of Harar's cultural heritage This architectural form is typical, specific and original, different from the domestic layout usually known in Muslim countries. It is also unique in Ethiopia. Harar was established in its present urban form in the 16th century as an Islamic town characterized by a maze of narrow alleyways and forbidding facades. From 1520 to 1568 it was the capital of the Harari Kingdom. From the late 16th century to the 19th century, Harar was noted as a centre of trade and Islamic learning. In the 17th century it became an independent emirate. It was then occupied by Egypt for ten years and became part of Ethiopia in 1887. The impact of African and Islamic traditions on the development of the town's specific building types and urban layout make for the particular character and even uniqueness of Harar.

Tiya Stelae

The stelae from the Soddo region, with their enigmatic configuration, are highly representative of an expression of the Ethiopian megalithic period.

Soddo lies to the south of Addis Ababa, beyond the Aouache river. It is remarkable because of the numerous archaeological sites of the megalithic period, comprising hundreds of sculptured stelae, that have been discovered there. The carved monoliths vary in size from 1 m to 5 m. Their forms fall into several distinct categories: figurative composition; anthropomorphic; hemispherical or conical; simple monoliths. In the northern area are to be found stelae with depictions of swords, associated with enigmatic symbols and schematic human figures.

Among the most important of the roughly 160 archaeological sites discovered so far in the Soddo region is Tiya, lying 38 km south of the river, which is also one of the most representative. Roughly aligned over an axis of 45 m there is a group of 33 stelae, with another group of three stelae a short distance from them. Of the 36 stelae at Tiya, 32 are sculpted with vaguely representational configurations (including the sword designs), which are for the most part difficult to decipher. One depicts the outline of a human figure in low relief.

They are the remains of an ancient Ethiopian culture the age of which has not yet been precisely determined. However, they have been interpreted as having a funerary significance, as there are tombs scattered around the stelae.

Konso Cultural Landscape

The Konso Cultural Landscape properties including the traditional stone wall towns (Paletea), ward system (kanta), Mora (cultural space), the generation pole (Olayta), the dry stone terracing practices (Kabata), the burial marker (Waka) and other living cultural practices are the reasons for the inscribiton of the Konso cultural landscape to be listed on UNESCO world heritage sites list. Cultural properties constituting the Konso Cultural Landscape are:-

- The traditional stone walled towns (Paletea) and their organization and associated cultural properties including the Kanta (Ward system), Mora(Cultural space), with its men house (Pafta), Generation marker tree (Olayta), erected stones (Daga-hela and Daga-diruma)

- The dry stone terrace( kabata), used for water and soil conservation

- The traditional maintained grooves (forests) which serve as a refuge for many endemic plants

- The burial marker statuettes (Waka) made of wood and unique to Konso people

- the ponds (Harda)

- The active traditions of Konso (erecting stelae)

Valley of Omo Pre-historic and Paleontological site

The areas of Omo Valley has internationally recognized as World Heritage site because of its outstanding paleo-anthropological and archaeological reserves. For instance, Omo, Fejej and Konso are among the prominent paleo-anthropological sites within and around the Omo valley. Sites of the Omo Valley contain fossil remains dating back to between 4 million and 100,000 years ago. Fossils of the genus Homo species and stone artifacts have been discovered in various localities including the following;

The partial skull of Homo habilis, dated to 1.9 million years ago

Homo erectus fossils dated about to 1.7 to 1.8 million years old

Fossils of modern Homo sapiens in the Kibish area; Homo sapiens were originated 100,000 years ago most likely in Africa.

Generally, many remains of humans and pre-human ancestors have been discovered in the Omo valley and the surrounding areas including Australopithecus Afarensis, Australopithecus aethiopicus, Australopithecusboisei, Homo habilis, Homo erectus, archaic and modern Homo sapiens

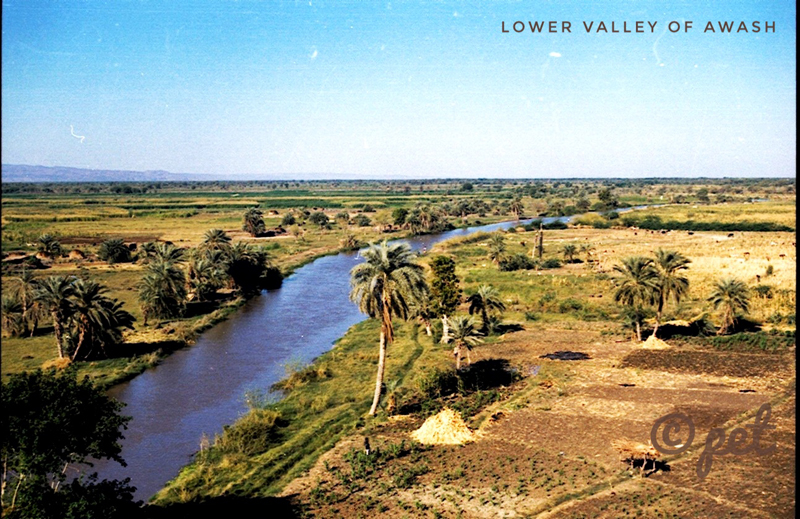

Valley of Awash; Paleontological and Pre-Historic Site

UNESCO registered the area of Awash Valley as a world heritage site mainly because of its immense paleo-anthropological and archaeological resources. In this regard, the Middle Awash, Hadar, Gona, Dikika, Busidima and MelkaKunture are worth mentioning. The Awash Valley contains the oldest hominid remains that date back at least to 5million years. It also provides evidence of the genus Homo sapiens and Lithic (stone tool) technology. The major fossil remains of the area are described in the table below.